NOTE: This article was originally published in October 2020.

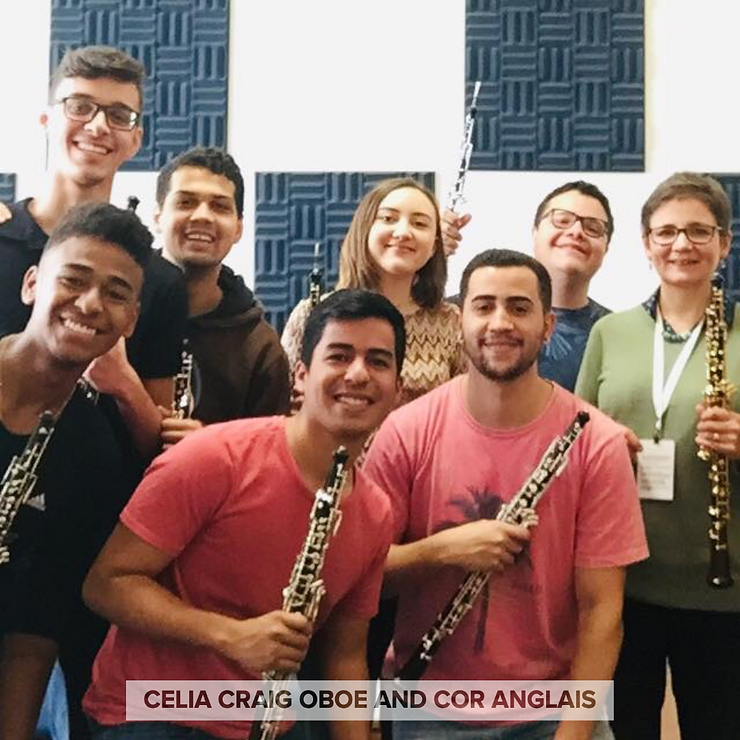

The young Brazilians I worked with were eager to play the oboe, share ideas and improve. They loved performing solo, preparing for their afternoon orchestra sessions, and making reeds.

I had four hours a day, from 9 AM till 1 PM, in a class where the students spoke little English. I was lucky to have great advice from a British colleague who spent two weeks teaching a class of clarinetists who didn’t speak a word of English! The experience highlighted the concept of music as a universal language—we communicate ideas by playing together.

Our eight players progressed during the two weeks through orchestral and solo music. We inhabited our own sonorous oboe room, with sounds of trombones and bassoons reverberating through the long corridor. We practised with a faculty flown in from all around the world. Lunchtimes (spent in the superb restaurant—no going outside without literally dodging bullets!) were vibrant with discussion about high standards and the children’s enthusiasm.

My talented class of oboists—Geiziane (back row, middle) will feature in the next instalment of my Brazil blog series.

The melting pot of staff defined the Baccarelli Institute’s ideals. People came from around the world: Paris, Cardiff, London, Amsterdam, Texas, Adelaide and Moscow, and the generous São Paulo orchestra members themselves (with whom we played enjoyable chamber music to a capacity crowd and a rock festival culture reception). The young people were all so keen to share their lives and discover ours, and stay in touch via social media—a “sociocultural” project indeed.

My experience in Brazil drilled in the notion that music is a universal language. We’ve all “conversed” with and understood sentiments from players and conductors without the need for talking. As a driver for societal change, the many cognitive and disciplinary benefits of performing music are clear, too.

I felt a bittersweet sadness about missing the last concert (Daphnis and Chloe, with exuberant Cuban conductor Giancarlo Guerrero!) for a pre-existing engagement in Sarajevo—and not only for the extreme hemisphere change.

My experience in Brazil drilled in the notion that music is a universal language. We’ve all “conversed” with and understood sentiments from players and conductors without the need for talking. As a driver for societal change, the many cognitive and disciplinary benefits of performing music are clear, too.

I’d learnt so much from teaching these players. Every fragmented conversation about their enthusiasm for musical study, and how lucky we all were to be part of this wonderful program, had a lasting effect on me.

Many of our players started with free instruments provided by Baccarelli and other similar projects. They now had dreams to become professional oboists and were keen on further study. I was invited to create links across the globe with courses, teachers, auditions and references. The system prepared them well. The students are now experienced and motivated musicians, well on their way to a professional music career.

The program encapsulated the principle of music as a catalyst for social change. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could have a similar program in South Australia?

“It is magical. What they do is fantastic … one of the most important cultural projects (for) young people in vulnerable social situations … values like self-discipline, respect, creativity, camaraderie and a sense of collaboration: essential for the education and development of any citizen in our society … Art is the best education,” said Luci Arena, a São Paulo school director. “Music helps develop attention, discipline and peaceful coexistence.”

To keep up to date on stories about Celia’s world travels and the value of music education, subscribe to our database here.